By Roger Helm (11 February 2016)

“What the heck is that?” “Way cool, look at those teeth?” “Eewh, everything is covered in slime?” “They’re all so tiny… oh, except for that shark, what kind is it?” “Wow, this is really amazing!” “There must be a mile of salps here?” “Are those myctophids?” “That is so weird looking, what is it?” “Who wants to help me figure out what these species are?” “Did anyone bring a copy of Fitch and Lavenberg’s Deep Sea Fishes or Miller and Lee’s California Fishes?” “Hey, pass me that Light’s Manual, I’ll try to figure out what some of these inverts are?” I think this is perhaps why Dr. G. Victor Morejohn got into teaching; it’s really fun and invigorating to be surrounded by a bunch of students delighting in new discoveries.

It was around midnight and we had just brought the cod end of a trawl net into the make shift fish lab we set-up on “The Rolling O” and spilled the haul onto a big waterproof table. The students in Dr. Morejohn’s Marine Birds and Mammals class, at least those that were still awake or not too seasick, were swarming around the table excitedly touching, warily poking, uncertainly watching, and generally being amazed by what was sloshing around in front of them. As the graduate student assistant for the class, I was grinning from ear to ear watching the students applying what we had been teaching them for the past several months as they sorted through the mess of flopping and oozing flesh. We hadn’t caught a Great White Shark, but the students seem no less thrilled by all the bizarre, colorful, and otherworldly creatures they were now cataloging.

It was April 1978, and we had taken the class on a three day cruise on “The Rolling O” to the waters off Año Nuevo Point just north of Monterey Bay in the hopes of hooking a Great White Shark. Each year these fearsome predators come to Año Nuevo to sink their massive jaws into an unsuspecting Northern Elephant Seal. The seals, which can weigh several tons, frequent Año Nuevo in winter to breed and return in spring through summer to molt.

Much to the delight of his students, and me, Dr. Morejohn had somehow convinced then MLML Director Dr. John Martin that a three day cruise on “The O” was a necessary field component to the Marine Birds and Mammals class he was teaching that spring. While the cruise did provided Dr. Morejohn and I ample opportunity to find, identify, and share with the students a great variety of the abundant marine birds and mammals of the bay it also allowed Vic the chance to try and land a real prize, Carcharodon carcharias. Ever since the 1975 premier of Jaws that brilliant but very unsettling movie (I still hear that music every time I go swimming at night), marine biologist at institutions all along the coast had intensified their interest in the Great Whites off California.

Prior to the cruise, Dr. Morejohn had gotten Ted Brieling, the Lab’s maintenance guru at that time, to mold several pieces of 3/4” rebar into a large single hook and a 3-barbed treble hook. After steaming up to Año Nuevo in “The Rolling O” we started chumming and trawling a chunk of meat back and forth off the coast near the island. There was this constant tension on the boat between Dr. Morejohn and the skipper of “The Rolling O”, John Snodgrass, over how close to the shore we should be. Dr. Morejohn wanted to be as close to the shore as possible believing that increased our probability of attracting and hooking a Great White, while Capt. Snodgrass wanted to be well offshore so he wouldn’t snag our trawling hooks or worse, his keel. In the end, Vic won out, but John was probably right as eventually we ‘caught’ something that straightened our single hook and later snatched our treble hook.

In the late afternoon of Day 2 a particularly unusual albatross started flying up our chum line. None of us could identify the bird so I hurriedly, and somewhat apprehensively given that I suspected he had brought his shotgun along, searched the boat to find Dr. Morejohn. After about 10 minutes of searching I gave up and returned to the fan tail with my camera to at least get a photo or two of the bird. Unfortunately, the unidentified albatross had skipped town. A bit later Dr. Morejohn surfaced, he had been napping in the captain’s quarters, and we all puzzled over what species he had missed. In my absence, one of the students had snapped a few photos of the bird and a few weeks later, after Kodak had done their thing, she handed me a few slightly blurry slides of our elusive albatross. After examining several sources we tentatively identified the bird as a Short-tailed Albatross and I sent off the slides and our observations to Dr. George Watson, an avian expert at the Smithsonian in DC. He confirmed our tentative ID which was quite significant since only a few hundred Short-tailed Albatrosses were known in the world at that time. This species, like all albatrosses, are very philopatric and after wandering far and wide for many years always return to breed at the colony where they hatched. Unfortunately for this species, their natal colonies were on Torishima, a small volcanically active island off Japan in which turn of the century eruptions had nearly extirpated these birds. This confirmation was very exciting and I wrote up a note on the sighting and submitted it to Western Birds with a copy of the photo. I was so proud of this note, my first ‘scientific publication’. Alas, the Short-tailed Albatross, like the Great White Shark trawling turned out to be a bust, as later another bird expert disputed the identification.

“The Rolling O” was not my favorite vessel. At 100’, the Navy owned harbor tug Oconostota was the largest vessel in the MLML fleet back in the late-70s. Acquired on loan from Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, this round keeled vessel was not at risk of flipping in heavy seas, but it constantly rolled in any seas. For about ½ the students in our class, and their graduate student instructor, the constant movement of “The Rolling O” was not appreciated by our inner ears and it resulted in many a distressed stomach. Nevertheless, despite all the logistical challenges, disappointments, and gastrointestinal upsets, this cruise was one of my highlights at MLML and based on class evaluations it also was a huge hit for the students fortunate enough to be enrolled that semester. Dr. Morejohn was a constant fountain of information and entertainment at the bow, the fan tail, and in the mess. The students saw over 70 species of birds, thousands of brown jellyfish, hundreds of deepwater fishes and inverts, a few secretive Harbor Porpoises, and large numbers of Blue Sharks, California Sea Lions, Harbor Seals. Elephants Seals, and bow riding Dall’s Porpoises. While we never hooked, much less landed, a Great White I have often wondered whether that may have actually been a good thing. Imagine if you will “The Rolling O” doing its crazy topsy-turvy thing in 5’ seas as the crew drags a thrashing, teeth gnashing two ton Great White Shark onto the slippery fantail while a gaggle of slightly to very ill landlubber students mosh in for a closer look….. hmmm.

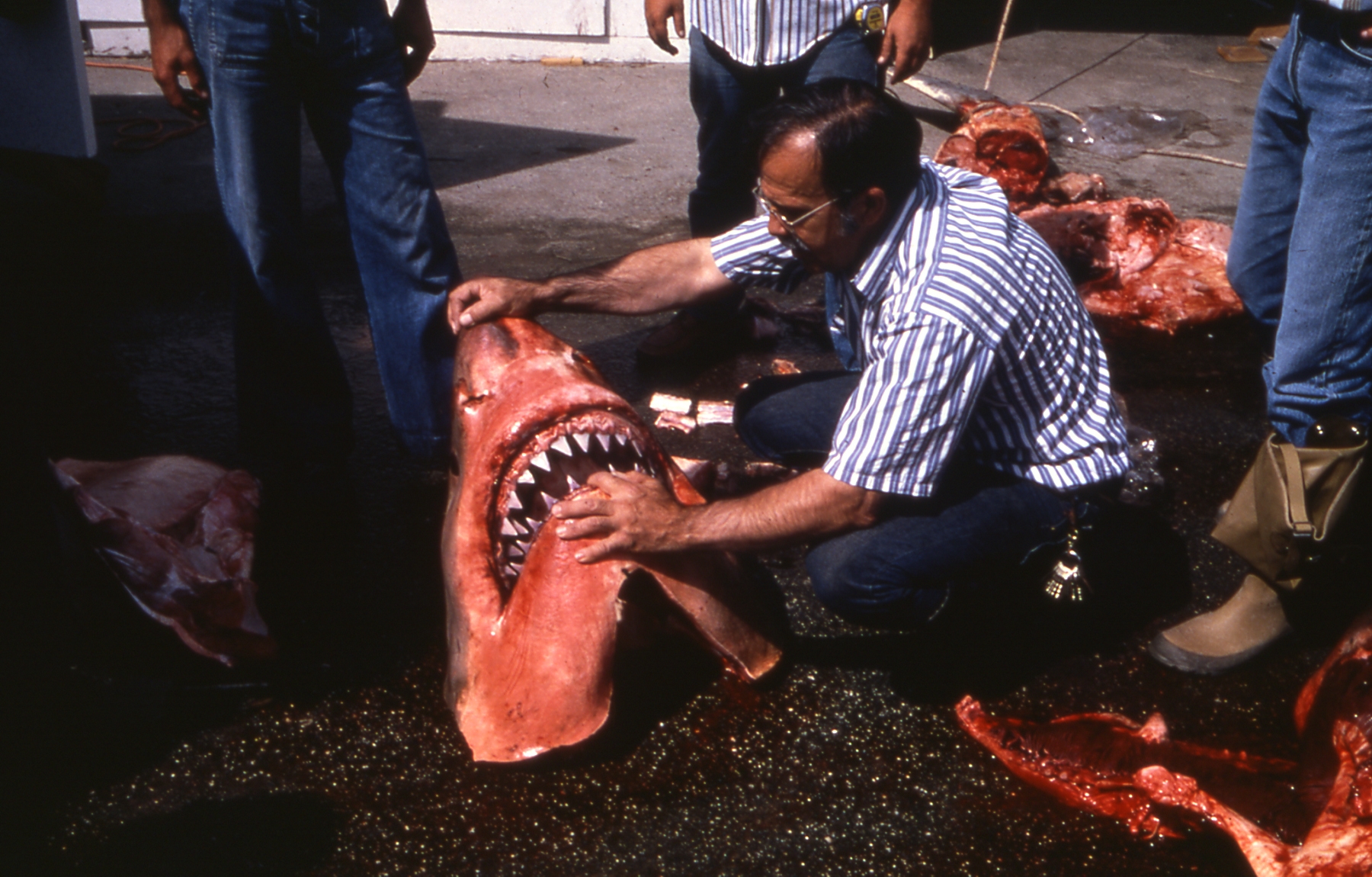

Post-Script: Six months after our cruise a 3m Great White was caught by fisherman and brought to the lab. Its stomach contained an intact adult harbor seal and Dr. Morejohn finally obtained the prized formidable jaws from a Great White.