By Shelby Penn, MLML Phycology Lab

By Shelby Penn, MLML Phycology Lab

As a child, I remember spending hours collecting trash from the street ditch, woods, and ravine around my house. It was something that I felt very strongly about even as an 8-year old. I’ve never been able to understand how someone could just throw their trash out the car window without a second thought. Today, as an avid outdoor enthusiast, tour guide, and lover of all things nature, or as I like to call it “neature”, helping out mother nature has now become a passion and life-long pursuit.

Chemical pollution is a huge problem across the globe and many contaminants are released into the natural environment daily. Concern over chemical pollution can be dated back as far as the 13th century when England’s King Edward I wanted to use penalties to reduce air pollution if the residents of London did not stop burning coal. This threat, however, had little effect, and it was not until after the industrial revolution that the concern of pollution resurfaced.

The issue of pollution resurfaced in the media when Rachel Carson published Silent Spring in 1962. In Silent Spring, Carson not only exposed the negative effects of DDT, a strong pesticide that affected dozens of species and most notably the bald eagle, but she brought public awareness to the negative impacts humans were having on the environment. This radical book for its time helped establish a framework and launch point for the environmental movement. With the publication of Silent Spring, government agencies around the world started making strides to reduce pollution and fight for environmental protection.

Some pollution, like trash, can be easier to remove from the environment, but more innovative ways must be used to remove chemicals and toxins. Bioremediation is the process of using plants, algae, and microorganisms to remove contaminants from the environment. The concept of bioremediation is credited to George Robinson and dates back to the 1960s. Today it is used at places like wastewater treatment plants and in composting.

Current bioremediation research has started to focus on possible methods for dissolved metal removal in marine and aquatic environments. To visualize this process, imagine while baking, some flour spills on the counter. It’s pretty easy to wipe up the spill and place it in the trash, right? Now imagine you spilled some of that flour into a cup of water, as you can probably tell, things are starting to get a little more difficult. Finally, now think about how hard it would be to remove hundreds of pounds of flour from an entire ocean, and I think you can get the picture: once mixed, it is so much harder to get back. Just like the flour, the removal of these metals from water can be particularly challenging because once they have become mixed into the water column, it is nearly impossible to remove them.

Cue the seaweed!

One suggestion for this problem is to use seaweed. Some species such as sea lettuce (Ulva spp.), have been shown to passively accumulate metals such as iron, lead, copper, zinc, cadmium, chromium, nickel, calcium, manganese, and mercury. These studies suggest that the presence of the seaweed itself might act like a sponge and soak up the dissolved metals. The hope would be to develop a method that would allow us to collect these metals accumulated by the seaweed, almost like wringing out a sponge.

A study by Henriques and colleagues tested the removal of mercury from contaminated water by three species of seaweed found off the coast of Portugal. The researchers tested the removal rates of living samples of seaweed from each of the major groups: red, green, and brown. The researchers found that the green algae removed almost 99% of the mercury in the water samples within 72 hours! Once the algae were removed from the water samples, the final levels of mercury in the solutions were equal to or lower than the legal limit for drinking water. The results of this study suggest that seaweed could be used as an efficient and cost-effective treatment of water contaminated with mercury.

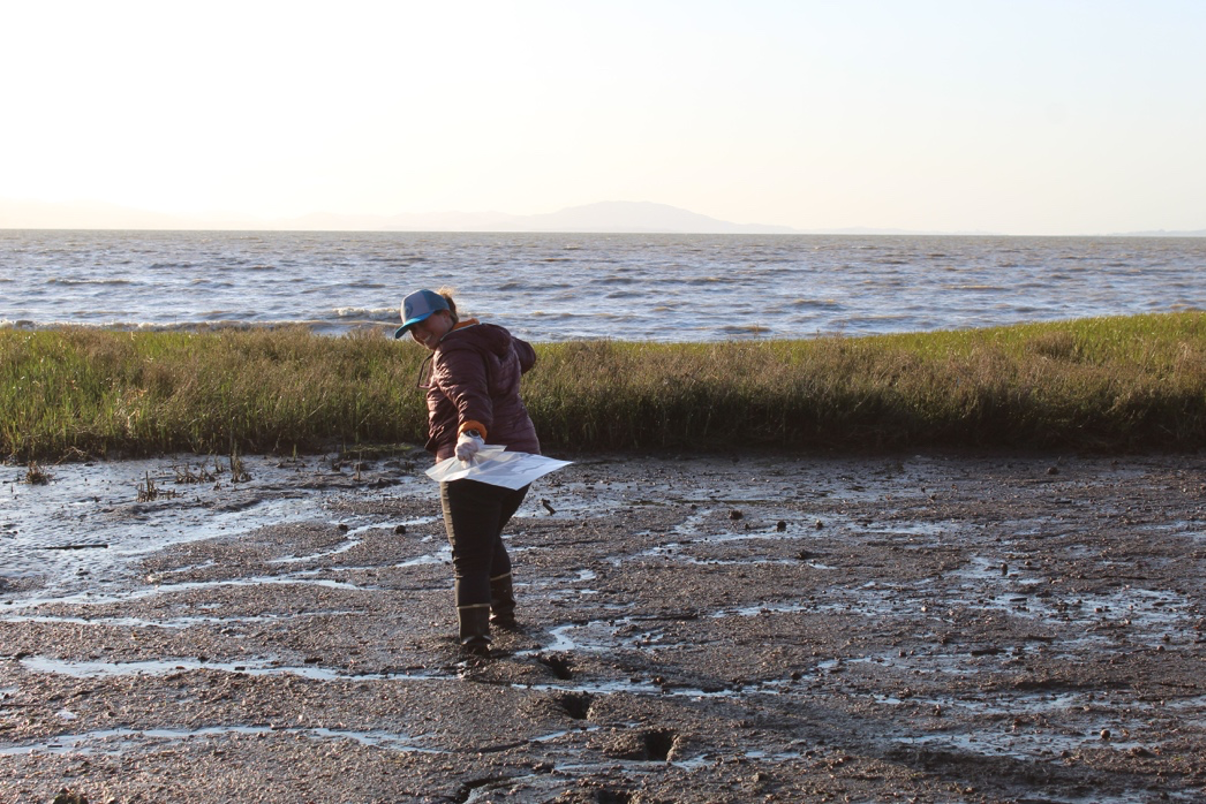

Here in California, the gold rush that occurred in the Sierra Nevada Mountains resulted in a huge loss of mercury to the environment. Mercury was used extensively to enhance the recovery of gold at hydraulic mines and it is estimated that eight to nine million pounds of mercury were used during the gold mining in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Today, this mercury continues to wash into the San Francisco Bay every time there is a rain or snow event. This influx has caused the mercury concentrations in species throughout the San Francisco Bay to increase, resulting in advisories for seafood consumption by the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. Since sea lettuce grows naturally throughout the San Francisco Bay Delta and it has been shown to accumulate mercury in short periods, it is possible this species could be used to remove the mercury that continues to wash into the Bay as a result of the gold mining. This process could be one small step toward regaining mercury lost in the gold mines.

My current research in the MLML Phycology Lab builds off of these previous studies and involves trying to understand what makes the sea lettuce so absorbent, like a sponge, to mercury. Hopefully, we will soon be able to better understand what specifically makes the algae so powerful for dissolved metal accumulation. If only my 8-year old self could see me now, I think she would be pretty happy.