By Sharon Hsu

Moss Landing has had a series of faculty retirements in the last year, including many who have been a part of the local community for decades. Kenneth Coale has long been synonymous with the lab space, helping students in the shop and forever carrying his coffee mug down the hallway. While we welcome this influx of new blood in the near future, we feel keenly the loss of familiarity and trust. Sharon Hsu, a student in the Vertebrate Ecology lab, wrote this piece to read aloud during Kenneth's retirement party. It echoes a sentiment many of us in the student body feel keenly. - Amanda Heidt

I’m really mad at Kenneth.

Wait, let me explain.

The first time I met Kenneth, he was shining a laser pointer on giant squid in a plastic tube. I had seen him before, in the hallways, making what I know now are trips to the staff room coffee pot, but I’d never spoken with him before.

I said, “What are you doing?”

Kenneth didn’t even bat an eye and went smoothly into an explanation about how the blue laser could penetrate much further in the liquid while the green (and this is where he nonchalantly took out another laser pointer) did not.

What I would come to learn is that this interaction summed up so much of what we the students (and let’s be honest… everyone else as well) love about Kenneth – his ability to teach and explain, without pushing or judging.

What I would come to learn is that this interaction summed up so much of what we the students (and let’s be honest… everyone else as well) love about Kenneth – his ability to teach and explain, without pushing or judging.

Months after this first meeting, I found myself in Kenneth’s Chemical Oceanography class. His first announcement in Chemical Oceanography was, “You’re only going to do as well as you want to in this class.” And this was the most amazing thing anyone has ever said. Because honestly, it’s amazing to have someone who wants to teach you things yet has the patience and belief that you can learn and do on your own accord. I like to think that what Kenneth was implying was, “You’re only going to do as well as you want to in life.”

So it’s not just the academic teaching that we love. It’s also just Kenneth – how he checks in to make sure we are okay. Because honestly, being okay is difficult sometimes, especially for grad students. Sometimes checking in is easy. Once on a boat trip in the Slough, half of the boat ended up clothed in extra jackets Kenneth had brought along. And once, checking in involved Kenneth single-handedly combating the housing crisis and temporarily adopting homeless students.

Sometimes, however, checking in is a little more difficult. More than once I have heard Kenneth tell us that the faculty is here to support us and not put us down, and more than once he has offered to listen to students who are feeling lost or down. And whether or not we choose to talk, just to have someone – and especially someone who could just as easily not have the time - offer to listen, means everything.

And now…. Kenneth is retiring. We are looking for a new faculty chemical oceanographer. Candidates have been chosen, interviewed, and evaluated. As students, we are also asked for our evaluations. And as a student, I really don’t feel qualified to evaluate any candidate’s academic merit. The only thing I can evaluate is how any new faculty member might interact with students. Will they understand the grad student struggle? Will they care? Will they make me feel comfortable talking to them about things I might be struggling with?

And now…. Kenneth is retiring. We are looking for a new faculty chemical oceanographer. Candidates have been chosen, interviewed, and evaluated. As students, we are also asked for our evaluations. And as a student, I really don’t feel qualified to evaluate any candidate’s academic merit. The only thing I can evaluate is how any new faculty member might interact with students. Will they understand the grad student struggle? Will they care? Will they make me feel comfortable talking to them about things I might be struggling with?

Quite frankly, I’m a little skeptical, which is not to say I can’t be won over. But there it is. I’m mad at Kenneth because he’s leaving. I’m mad that the new students won’t be able to take Chem Oce or shop class with him. I’m mad that we’ll see less of him shining laser pointers at dead squid, and I’m mad that trips in the Slough sampling swirling vortexes will end, along with using calculators to calculate the slope of a line and jeopardy using the loudest metal objects as buzzers. I’m mad there will be one less faculty member that says, “I’m available. You can email me or call me. Here are all my phone numbers.” And I’m mad that no one is going to start off another class saying, “You’re only going to do as well as you want to in this class.” I’m mad that we may be losing one of the biggest champions of the students.

So yeah, I’m mad. But mostly, I’m thankful.

Can the words “thank you” sum up everything we want to say to Kenneth Coale?

I don’t think so, but I’m not sure what else we can say.

Thank you, Kenneth, for your patience.

Thank you, Kenneth, for your kindness, and your willingness to be a champion of the students.

Thank you, Kenneth, for keeping an eye out and making sure we are okay.

Thank you, Kenneth, for teaching us – about chem oce, but more importantly, about life.

Thank you, Kenneth, for showing us what we can strive to be.

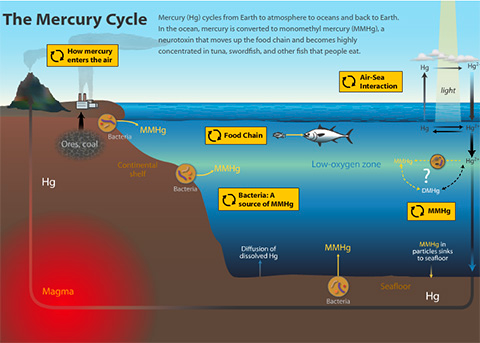

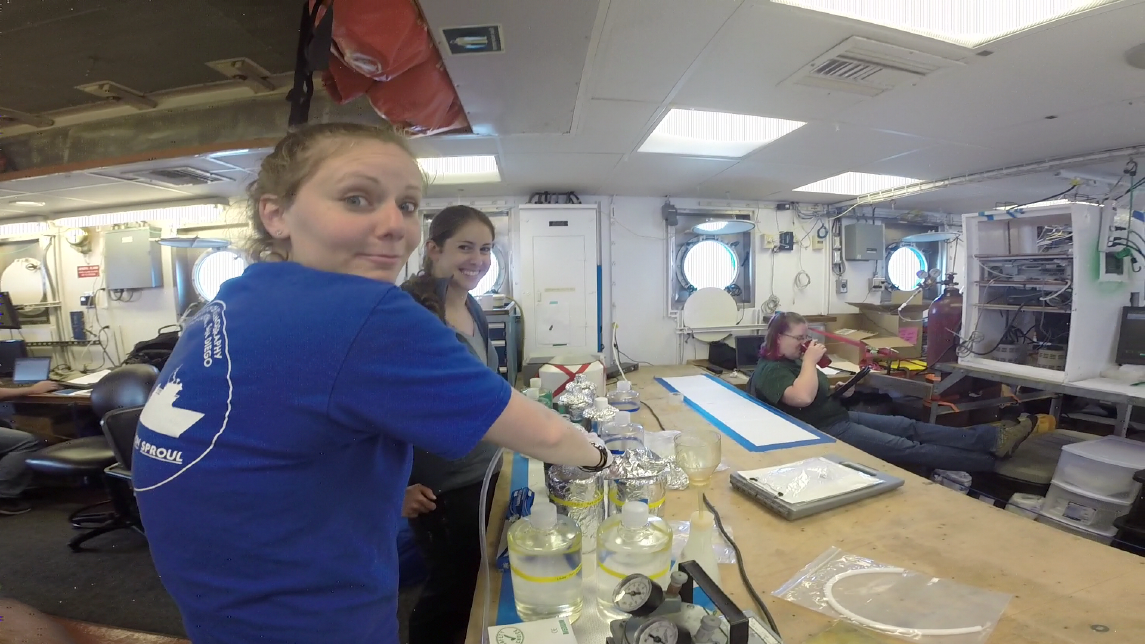

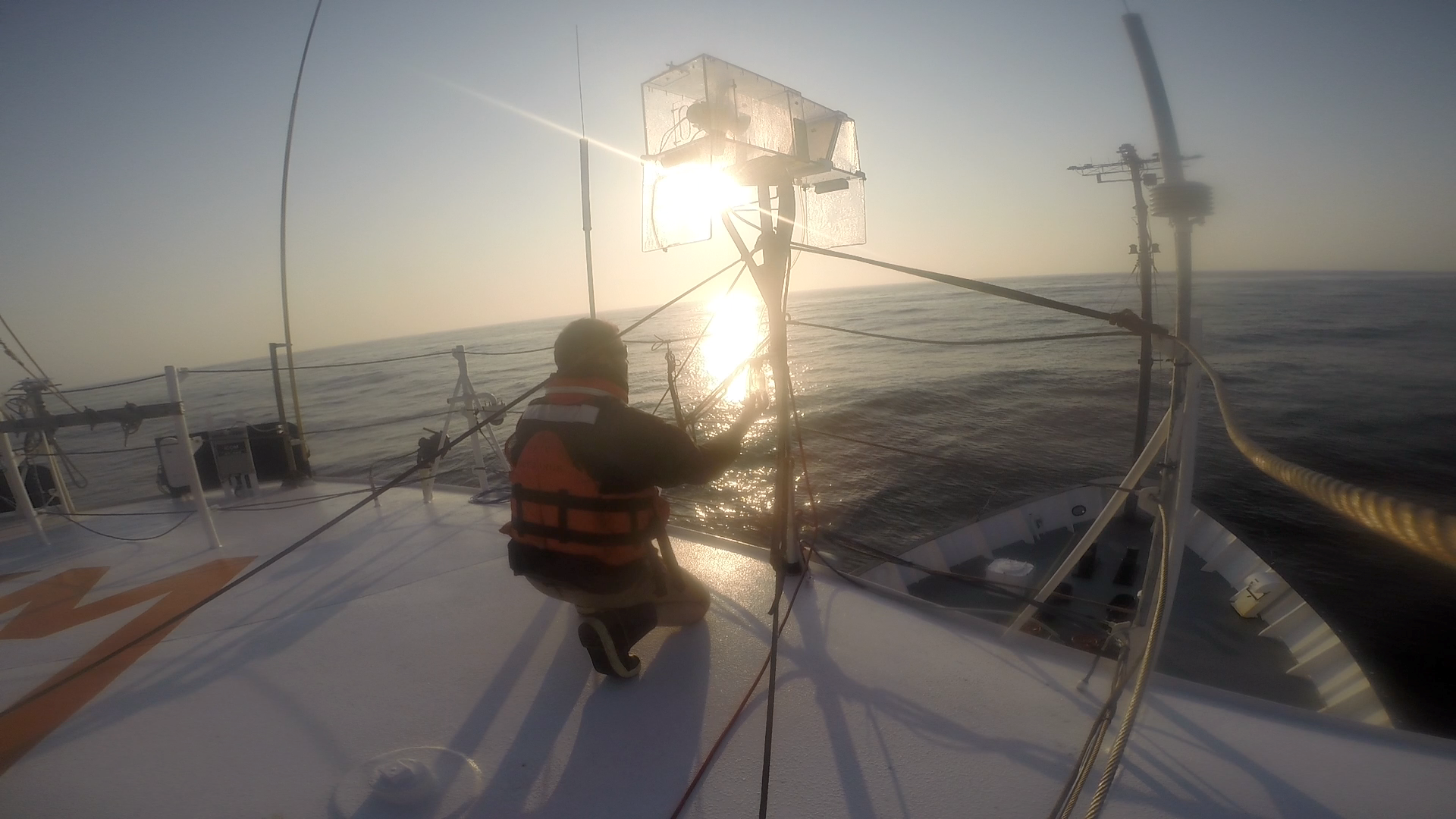

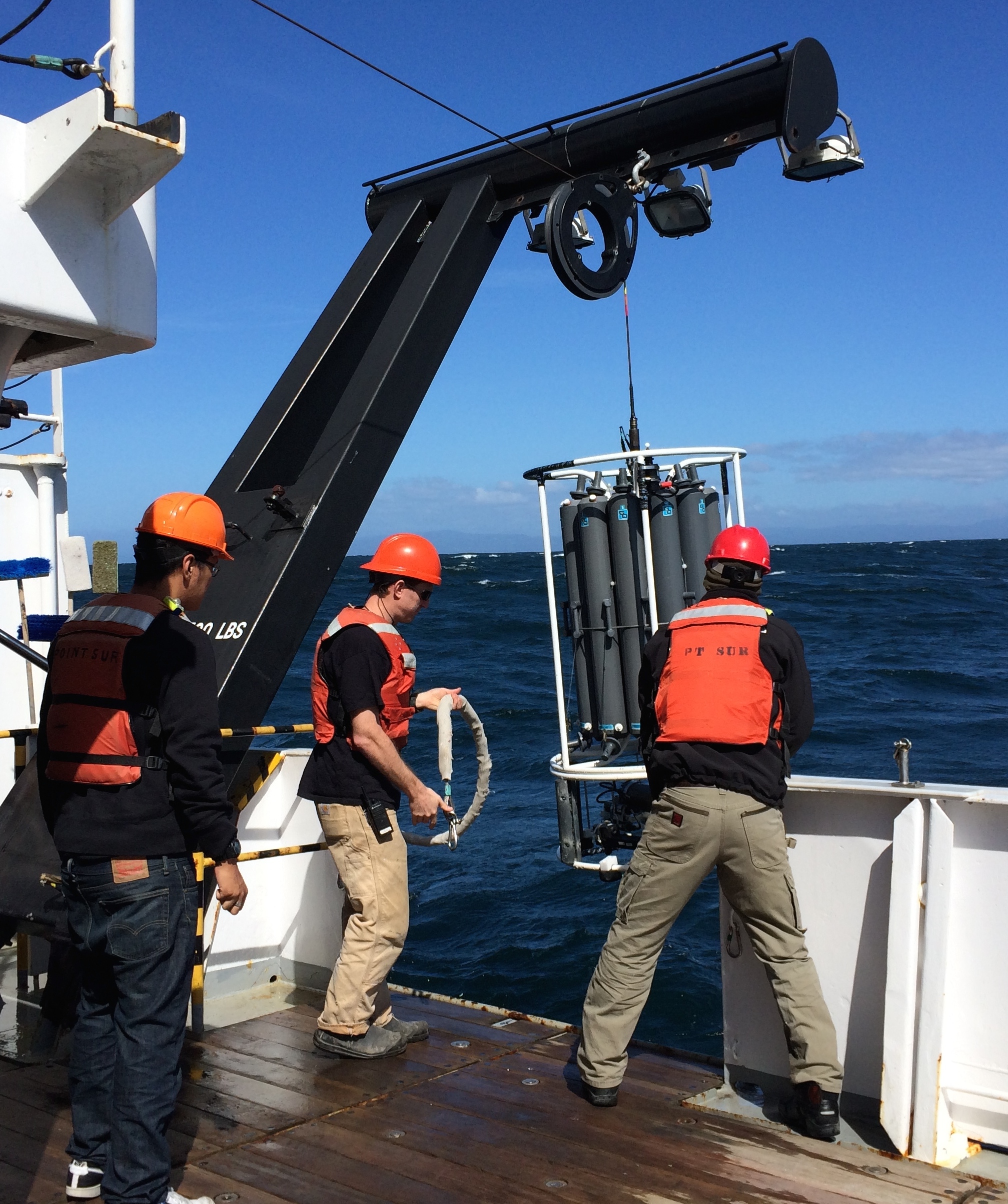

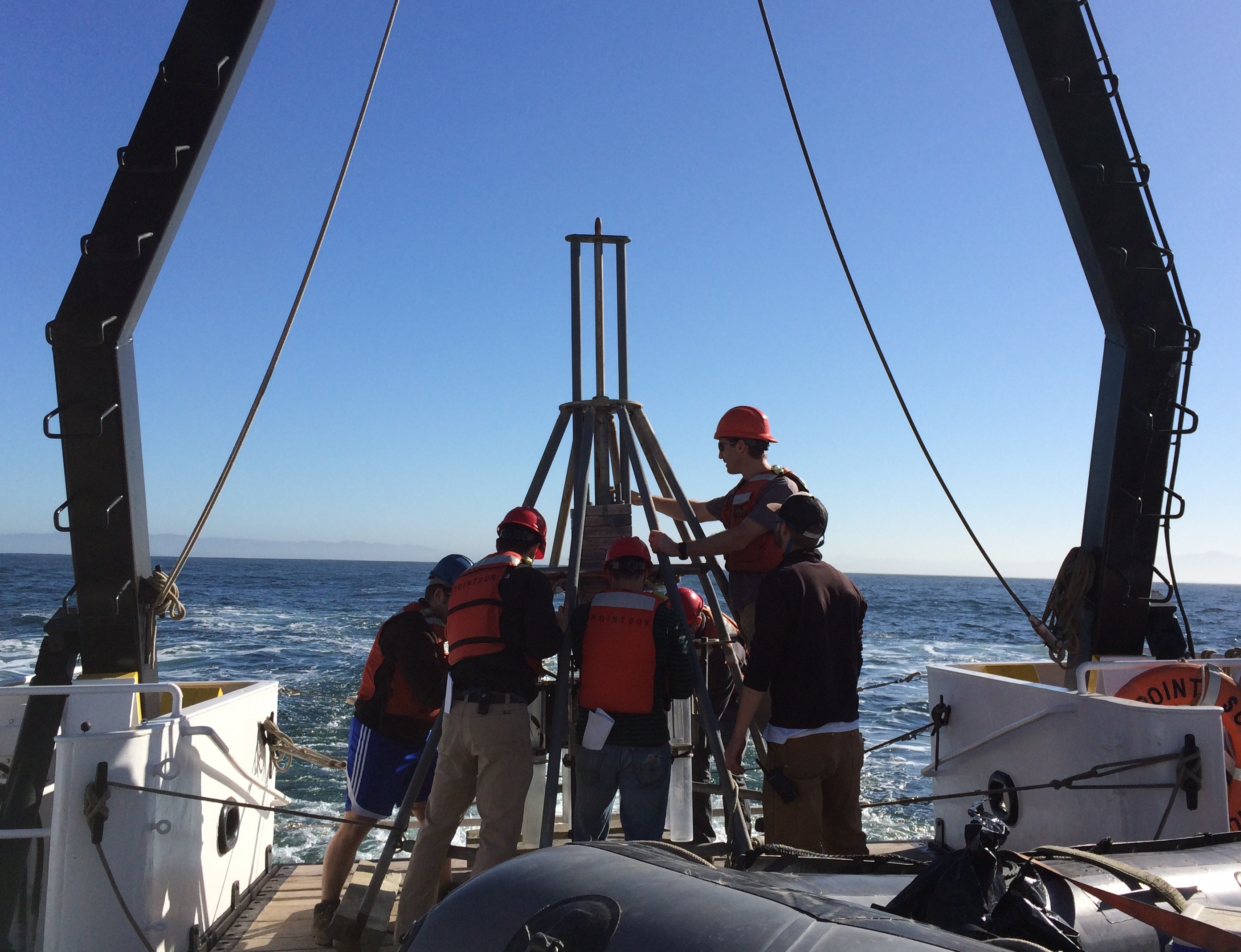

By Erick Partida, MLML Chemical Oceanography Lab

By Erick Partida, MLML Chemical Oceanography Lab

What I would come to learn is that this interaction summed up so much of what we the students (and let’s be honest… everyone else as well) love about Kenneth – his ability to teach and explain, without pushing or judging.

What I would come to learn is that this interaction summed up so much of what we the students (and let’s be honest… everyone else as well) love about Kenneth – his ability to teach and explain, without pushing or judging. And now…. Kenneth is retiring. We are looking for a new faculty chemical oceanographer. Candidates have been chosen, interviewed, and evaluated. As students, we are also asked for our evaluations. And as a student, I really don’t feel qualified to evaluate any candidate’s academic merit. The only thing I can evaluate is how any new faculty member might interact with students. Will they understand the grad student struggle? Will they care? Will they make me feel comfortable talking to them about things I might be struggling with?

And now…. Kenneth is retiring. We are looking for a new faculty chemical oceanographer. Candidates have been chosen, interviewed, and evaluated. As students, we are also asked for our evaluations. And as a student, I really don’t feel qualified to evaluate any candidate’s academic merit. The only thing I can evaluate is how any new faculty member might interact with students. Will they understand the grad student struggle? Will they care? Will they make me feel comfortable talking to them about things I might be struggling with?

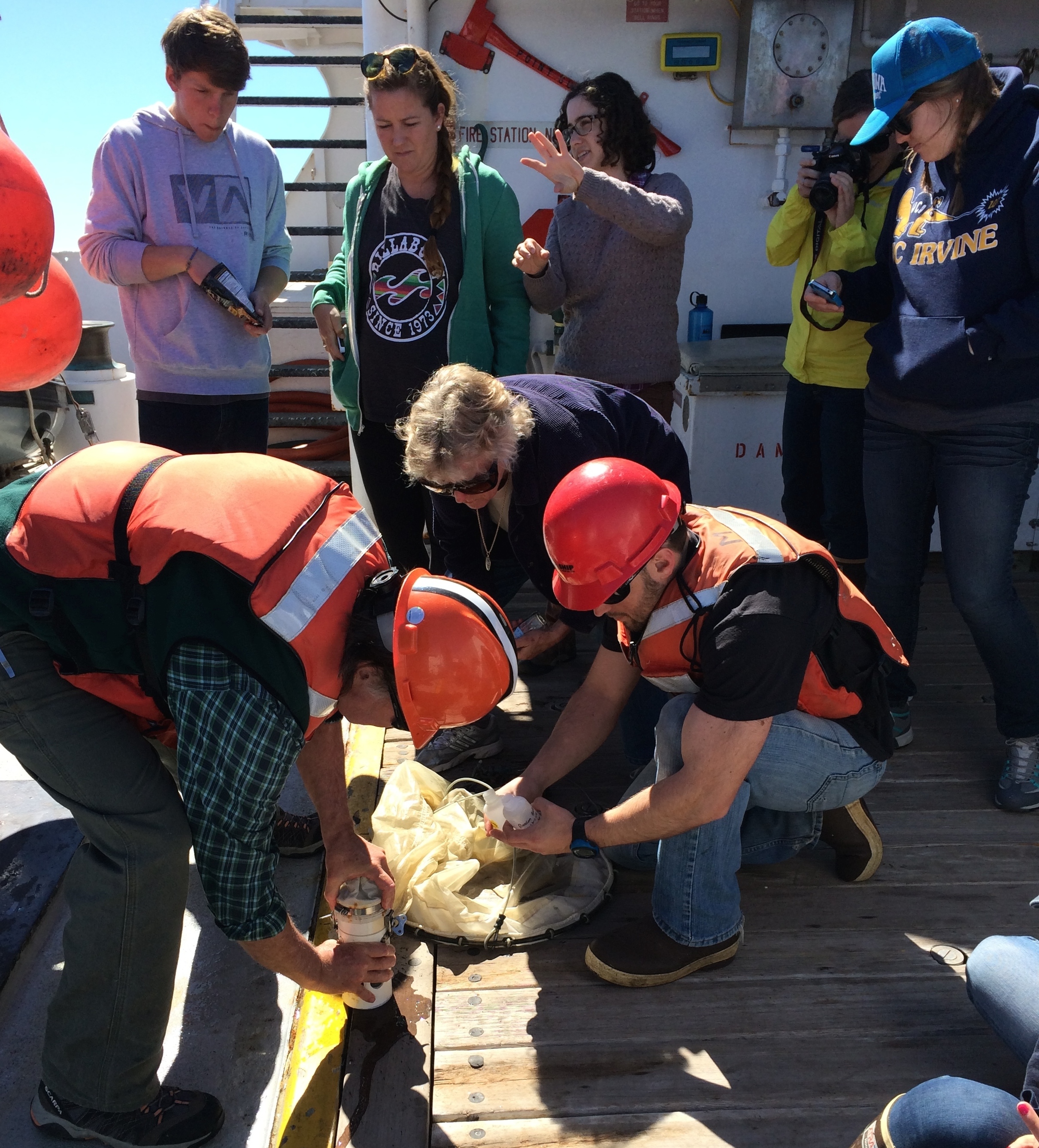

Overall, it was an amazing experience. I learned a great deal by choosing a project not in my area of expertise and expanded my worldview... all while getting a tan! Who’s up to take the trip again?

Overall, it was an amazing experience. I learned a great deal by choosing a project not in my area of expertise and expanded my worldview... all while getting a tan! Who’s up to take the trip again?