By Lauren Parker, MLML Ichthyology Lab

By Lauren Parker, MLML Ichthyology Lab

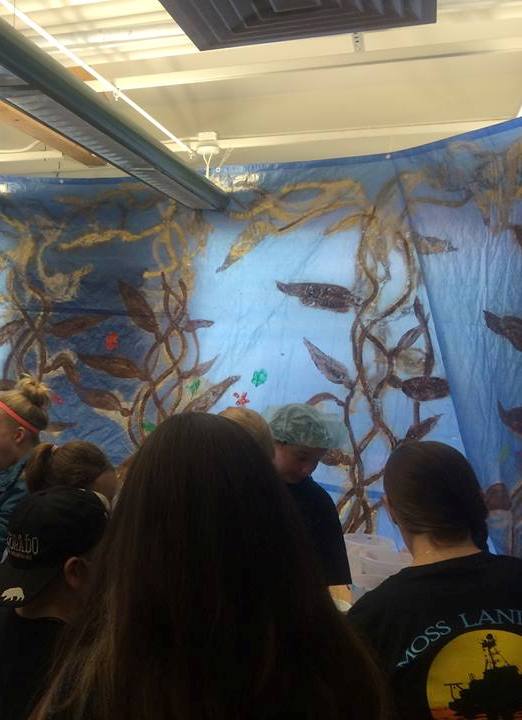

I can’t tell you how much I miss spending the majority of my day underwater. It’s difficult to communicate the feeling it gives you; the feeling that you have somehow been given the opportunity to glimpse another world, one that most people never get to see. As a marine scientist spending a select few glorious (for the most part) hours in that world, I am tasked with collecting data. I record pages and pages of species codes and numbers, I count things and I measure them. I take copious amounts of photos.

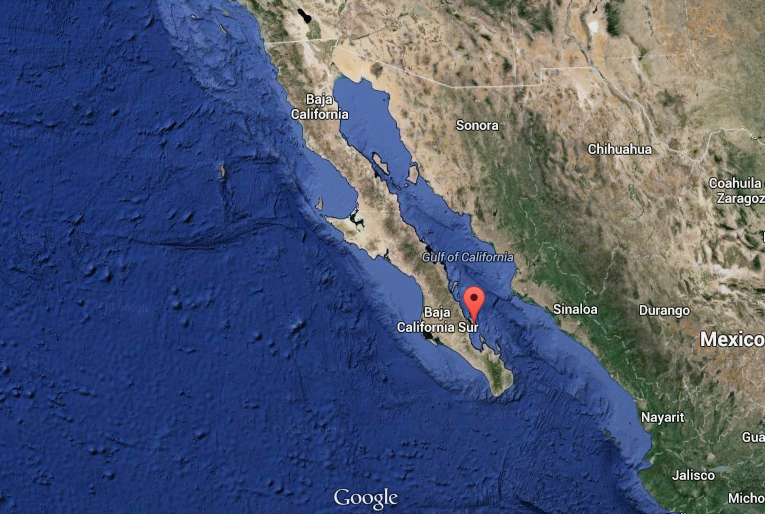

I was a research SCUBA diver for the Partnership for the Interdisciplinary Studies of Coastal Oceans (PISCO) at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), monitoring the kelp forest around the northern Channel Islands in Southern California. Most of my days were spent waking up before the sun, loading dive gear into the boat, racing dolphins and dodging migrating whales across the Santa Barbara Channel so that we could dive all day long. We’d race the sunset back to the harbor just to do it all again the next day.

UCSB’s PISCO team has been monitoring the kelp forest in the Channel Islands since 1999. While changes over the long-term are the principle focus of organizations such as PISCO, short-term variability in ecosystem structure can provide insight into the potential effects of future ocean conditions, particularly in the context of a swiftly changing climate.

While my time with PISCO represents just a snapshot of the continually evolving story of the kelp forest ecosystem, I was witness to several distinct changes in the kelp forest community in my five seasons of diving. I watched sea star populations decline markedly and sunflower sea stars disappear completely. I watched the invasive alga, Sargassum horneri, replace the native giant kelp at Catalina Island and then quickly spread to the northern Channel Islands. More and more often we recorded species not normally seen on our surveys.

Decline in Sea Stars

I began surveying the kelp forest in 2013, just before the anomalous rise in sea surface temperatures across the North Pacific Ocean, known as the “warm blob,” appeared along the west coast. For a more in-depth explanation of the “warm blob” check out this link. 2013 was also the last year during which I saw a sunflower sea star.

Sunflower sea stars can grow up to meter in diameter, and can have 24+ arms as adults. They are also voracious predators, feeding on a variety of invertebrates and even other sea stars. Sunflower sea stars were seemingly the first casualty in what came to be a mass mortality event over the next few years. Sea Star Wasting Disease (SSWD) caused the death of many types of sea stars and scientists are still studying the disease’s origins and what triggered the outbreak. Sunflower stars play an integral role in the kelp forest ecosystem. As sunflower stars became functionally extinct, purple urchin numbers increased dramatically, which in turn caused a marked decline in kelp abundance, though not as prevalent a decline as that of macroalgae populations in central and northern California. While noted as an important player in the kelp forest, research on sunflower sea stars is unfortunately minimal due to a lack of commercial importance.

A large number of other sea star species were heavily impacted by SSWD. The ochre sea star, the giant-spined sea star, and the short-spined sea star are larger and more abundant species, so their decline was particularly apparent. These and several other sea stars, totaling around twenty different species, were decimated by SSWD. Infected individuals looked like they were slowly dissolving, many of them missing limbs and they were often covered in white, fleshy lesions.

Invasion of Sargassum

Sargassum horneri, nicknamed devil weed, is an invasive seaweed native to eastern Asia and a relatively new resident in California waters. Discovered in 2003 in Long Beach harbor, it has since invaded and become established throughout Southern California, taking a particularly firm grip in the Channel Islands. S. horneri has become the subject of several studies aimed at understanding it’s invasibility, particularly its ability to outcompete native algae. In the northern Channel Islands, at Anacapa Island in particular, the level of invasion has been linked to the level of management, where marine protected area type and the length of protection strongly influence invasibility. Results indicate that marine invasions are complex but that protection does play a key role in resistance. Check out this paper for more information. Adequate marine management is imperative in a changing climate, particularly since marine invasions are forecasted to increase with changes in ocean climate.

An increase in ocean temperatures is often accompanied by some odd animals showing up in strange places. This became particularly apparent during the “blob” years of 2014 through 2018 when a variety of organisms began pushing the limits of their typical temperature envelopes and causing an uproar wherever they were spotted. Thousands of pelagic red crabs began making a regular appearance each field season. Finescale triggerfish began showing up on the same transects as lingcod, a comparably much colder water fish. A goldspotted sand bass, normally a resident of the waters from Cedros Island southward off the coast of Baja California, showed up on a fishing vessel in the Channel Islands. Basking sharks began patrolling the waters of the channel and green sea turtles were glimpsed at Santa Cruz Island. These examples represent only a portion of what seemed out of the ordinary during my time with PISCO. However, an increasingly changing ocean climate is likely to foster shifts in species ranges that will cause a lot more strange animals to show up in weird places. If you happen to see any such animals, such as the sheephead and spiny lobsters that have shown up in Carmel, check out the Strange Fish in Weird Places website and let the scientists know what you saw.

Return of top predators

Not all of the changes I witnessed were negative, although that might depend on who you ask. Recent years have shown what seems to be a recovery of top predators in the kelp forest ecosystem. Yep. You guessed it. Sharks. White shark populations have made a significant comeback, with higher numbers of both adult and juvenile populations reported along the California coast, likely the result of increased protections in the last couple of decades. While white sharks do pose a threat to crowded beaches and various other ocean pastimes, such as surfing and freediving, they are a vital component of the marine ecosystem and their increase in numbers, while making us ocean goers slightly more uneasy, should be celebrated.

These events by no means indicate a clear trend for the future of the kelp forest, however they do highlight what can happen in a drastically changing climate. Recent years, including those in which I was an active PISCO diver, were what can be termed a perfect storm of events. Periodically warmer waters caused by an El Niño event were coupled with the “warm blob”, a marine heatwave that caused unseasonably warm waters for an extended period along the west coast of the United States. Prolonged elevated temperatures caused innumerable marine impacts, and likely had a hand in the ones discussed here.

More frequent and more intense storms and heat waves, like the “blob”, higher levels of pollution, and other anthropogenic impacts that result from climate change are threatening ecologically and economically important marine systems, worldwide. Scientists in recent years have begun to confirm that kelp systems, globally, are in decline. The need for long-term monitoring of ecosystems is necessary now, more than ever, to assess and understand the changes that are happening right before our eyes.