by Grace Teranishi, MLML Ichthyology Lab

As marine scientists and scientists-in-training, we at MLML know we dodged a bullet in the decision against pursuing a career in, say, medicine—a path that inevitably leads to a hypochondriacal aunt listing her symptoms to you at the Thanksgiving table or to a patient of yours asking about his unfortunate toe rash when he spots you at self-checkout. Aren't you also glad you didn't major in studio art, which would have everyone and their mother wanting to hire you to illustrate a children’s book? Yes, we fish people, sponge people, seaweed connoisseurs, and sediment transport enthusiasts have it pretty good, but there are still a few comments and interactions we would prefer not to put up with on a day-to-day basis.

I asked MLML students, "What are you tired of people telling you because they know you are in the marine science field?" Here's what you had to say:

Some of you were frustrated that people underestimate the work you do.

1. "What an easy job/degree. You’re so lucky just hanging out at the beach all day." -Dylan, Ichthyology

Others of you have experienced that people vastly overestimate what you can do.

2. "'Oh you're a marine scientist, you're going to save the world.'

–there's literally no paper I could publish that would suddenly make people take environmentalism more seriously. The change has to come from policy. Also, assuming that the tanks in the [Monterey Bay Aquarium’s] deep sea exhibit are pressurized. They're not." -Alex, Invertebrate Ecology

3. "Oh, so you're going to save the coral reefs, right?" -Keenan, Invertebrate Ecology

We would love to reverse centuries of environmental exploitation with a snap of our fingers, but unfortunately, that’s not how it works.

Some expressed fatigue at general ignorance.

4. "Challenging if the megalodon is truly extinct because we've only explored 30% of our oceans." -Sophie, Marine Biology major at SJSU

We love a good bad shark movie now and then, but please stop.

Or fatigue at the nonstop questions not even remotely related to what you actually study.

5. "This one time during a dinner rush I was serving a large table and they asked me if I was in school. Upon finding out I was at MLML, one patron asked me to enlighten the table about the local ecology of the bay. 'Tell us about the canyon!' he said. 'Tell them about the whales!' he said. 'Twas dinner and a show... we were very busy... and I study fish genes." -Nick, Ichthyology

6. "I participate in Skype-a-Scientist, where you match with classrooms to talk about your experiences as a researcher. I introduced myself as a student at the Marine Labs with a focus on fish/estuaries/ocean life; I matched with an elementary school teacher who wanted me to answer an eight year-old's questions about platypuses." -Grace, Ichthyology

7. "So do you like, train dolphins?" -Jackie, Fisheries & Conservation Biology

8. "When you type 'phycology' into a google search and get asked if you really mean 'psychology.'" -Shelby, Phycology

9. "What kind of fish is this?" "How long can whales hold their breath for?" "Does toilet bowl water really go down counter-clockwise?" -Victoria, Geological Oceanography

People just really love hearing all about the sharks.

10. "It has to be 'Have you ever seen sharks?' when I talk about diving or am spotted with dive gear at a beach. Sometimes it is difficult to talk about them in a realistic, non-threatening way." -Kameron, Ichthyology

11. "Did you hear about the shark attack at [location]? What do you think happened?" -Matt, Phycology

Many of you were tired of talking to people about Monterey Bay sea otters and felt that the less charismatic ocean life deserved a little more love.

12. "*Looks at an invertebrate* ‘Wait, but they're not alive though right?'" -Noah, Invertebrate Ecology

13. "They always want to talk about sea otters and why they are so important here." -Amber, Vertebrate Ecology

14. "I'm tired of people thinking I study fish or mammals... or when people mention how their cousin studied marine biology in undergrad but now she's a *insert random unrelated profession*" -Jess, Phycology

There’s more to the ocean than whales and dolphins and otters, people!

And on a similar note, marine science encompasses so much more than just biology.

15."People asking what the difference [is] between marine science and marine biology" -Samuel, Ichthyology

16. "So you're a marine biologist?"' -Anonymous

17. "Everyone assumes I'm a 'marine biologist' when I tell them I'm an oceanographer :-)" -Marine, Chemical Oceanography

We are also not all out there telling everyone to stop eating fish. Sometimes it’s quite the opposite! We want to make sure that there’s still fish left in the ocean so we can keep eating them.

18. "Oh so fish science? Wait, do you still eat fish?" -Quinn, Ichthyology

19. "I study vertebrate ecology. People usually assume that I am extremely against all forms of fishing. I have a lot of respect for fishermen and want to help them as much as I want to protect endangered marine mammals and turtles."-Kali, Vertebrate Ecology

20. “If I eat fish and then [they] get surprised that I do. Of course I do they're delicious." -Konnor, Fisheries & Conservation Biology

Currently thinking about the trout I had for dinner last night.

And finally, this:

21. "'You will be paid in experience!' -with regard to any unpaid internship 'opportunity'" -Anonymous, Geological Oceanography

Thank you everyone for taking the time to respond to this survey!

By Acy Wood,

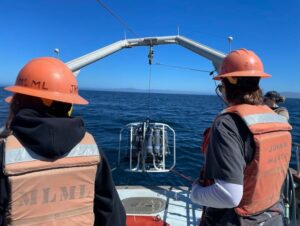

By Acy Wood,  The reliance on a single species means that researchers need to give special attention to the conditions that species thrives in. Any changes that the foundation species experiences will inevitably trickle down to the other community members. Going back to our example, if the kelp that make the kelp forest are unable to thrive, then the young rockfish will have to go somewhere else to hide. Oftentimes, underwater plants are sensitive to specific temperatures or specific depths. They may grow very well in places that have the right mix of conditions, but will no longer flourish if those conditions happen to change from what the plants need. Similarly, if an area nearby changes to suit them, then they can move right in.

The reliance on a single species means that researchers need to give special attention to the conditions that species thrives in. Any changes that the foundation species experiences will inevitably trickle down to the other community members. Going back to our example, if the kelp that make the kelp forest are unable to thrive, then the young rockfish will have to go somewhere else to hide. Oftentimes, underwater plants are sensitive to specific temperatures or specific depths. They may grow very well in places that have the right mix of conditions, but will no longer flourish if those conditions happen to change from what the plants need. Similarly, if an area nearby changes to suit them, then they can move right in. By

By